Mark Skousen, ed.

Dissent on Keynes:

A Critical Appraisal of Keynesian Economics

New York: Praeger Publishers, 1992, pp. 131-147

Is Milton Friedman a Keynesian?

Roger W. Garrison

He Isn't

But He Is He Isn't

But He Is

There is a story about a young job candidate interviewing for an entry-level

position in the geography department of a state university. One senior

faculty member, whose opinion of our modern educational system was not

especially high, asked the simple question, "Which way does the Mississippi

River run?" In ignorance of the biases of this particular geography department

and in fear of jeopardizing his employment prospects, the candidate boldly

replied, "I can teach it either way."

When the question "Is Milton

Friedman a Keynesian?" was first suggested to me as a topic, I couldn't

help but think of the uncommitted geographer. But in this case, opposing

answers can be defended with no loss of academic respectability. When teaching

at the sophomore level to students who are hearing the names "Keynes" and

"Friedman" for the first time, I provide the conventional contrast that

emerges naturally out of the standard account of the "Keynesian Revolution"

and the "Monetarist Counter-Revolution." To claim otherwise would come

close to committing academic malpractice. Either a casual survey or a careful

study of the writings of Keynes and Friedman reveals many issues on which

these two theorists are poles apart.

Yet, one can make the claim

that Friedman is a Keynesian and remain in good scholarly company. Both

Don Patinkin (Gordon, 1974) and Harry Johnson (1971) see Friedman's monetary

theory as an extension of the ideas commonly associated with Keynes. Some

of their arguments, however, run counter to those of the Austrian school,

which serves as a basis for this chapter. And while Friedman, by his own

account, was quoted out of context as saying, "We're all Keynesians now,"

his in-context statement is thoroughly consistent with an Austrian assessment.

More than two decades ago, during an interview with a reporter from Time

magazine, Friedman commented that "in one sense, we are all Keynesians

now; in another, no one is a Keynesian any longer." The two senses were

identified in his subsequent elaboration: "We all use the Keynesian language

and apparatus; none of us any longer accepts the initial Keynesian conclusions"

(Friedman 1968b, p. 15).

Patinkin and Johnson have

each argued that Friedman's attention to the demand for money, and particularly

his inclusion of the rate of interest as one of the determinants of money

demand, puts him closer to Keynes than to the pre-Keynesian monetary theorists.

Friedman has responded by insisting that the inclusion of the interest

rate in the money-demand function is a minor feature of his theoretical

framework (Gordon, 1974, p. 159). Austrian monetary theorists, who pay

more attention to the interest rate than does Friedman and as much attention

to it as did Keynes, have a different perspective on the interest-rate

issue. Both Keynes and Friedman have neglected the effects of change in

the interest rate on the economy's structure of capital. From an Austrian

viewpoint this sin of omission, which derives from a common "language and

apparatus," makes both Keynesianism and Monetarism subject to the same

Austrian critique.

Keynesianism: From the Treatise to the General Theory

It is important to note, then, that the sense in which the statement

"We're all Keynesians now" is true�from both a Monetarist and an Austrian

perspective�involves a circumscribed "all." Monetarists are included; Austrians

are not. Drawing out the essential differences among these schools of thought

requires that we begin by considering the common "language and apparatus"

that predates Friedman's (1969a) restatement of the quantity theory of

money and that predates even Keynes's General Theory. The Austrians

can be identified as Keynesian dissenters on the basis of Keynes's earliest

macroeconomics.

Keynes's two-volume Treatise

on Money, which appeared in 1930, was not well received by economists

who drew their inspiration from Carl Menger and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk.

Although the macroeconomics found in Keynes's Treatise is not readily

recognizable today as Keynesian theory, the theoretical building blocks

and methods of construction are largely the same. The macroeconomic aggregates

of saving, investment, and output are played off against one another in

a manner that establishes equilibrium values for the interest rate and

price level.

In an extended critique

of this early rendition of Keynesianism, F. A. Hayek found many inconsistencies

and ambiguities, but his most fundamental dissatisfaction derived from

Keynes's mode of theorizing�from his "language and apparatus": "Mr. Keynes's

aggregates conceal the most fundamental mechanisms of change" (Hayek, 1931a:

p. 227). Keynes had argued that changes in the rate of interest have no

significant effect on the rate of profit for the investment sector as a

whole. Hayek's point was that profit reckoned on a sector-wide basis is

not a significant part of the market mechanism that governs production

activity. A change in the rate of interest means that profit prospects

for some industries rise, while profit prospects for others fall. The systematic

differences in profits rates among industries, and not the average or aggregate

of those rates, are what constitute the relevant "mechanisms of change."

There were fundamental shifts

in Keynes's thinking during the six years between his Treatise and

his General Theory, but none that could be considered responsive

to Hayek's critique. In the General Theory, impenetrable uncertainty

about the future clouded the decision processes of investors and wealth

holders; the interest rate became a product of convention and psychology,

largely if not wholly detached from economic reality; changes in market

conditions were accommodated by income adjustments rather than price or

interest-rate adjustments; and unemployment equilibrium became the normal

state of affairs.

Selective readings of what

Keynes actually wrote�as well as creative readings of what he may have

intended to write�have given rise to conflicting interpretations of Keynes's

message. In many instances, disagreements about Keynesian answers to macroeconomic

questions derive from disagreements about what the relevant macroeconomic

questions are. Is Keynes asking: How, in particular, do markets actually

work? Or is he asking: Why, in general, do they not work well? More specifically,

does the interest-inelastic demand for investment funds enter importantly

into his theory, or does the instability of investment demand, driven as

it is by the "animal spirts" of the business world, swamp any consideration

of interest inelasticity? Does the highly interest-elastic demand for money

enter importantly into his theory, or does the instability of money demand,

based as it is on the "fetish of liquidity," swamp any consideration of

interest elasticity?

Interpreters such as G.

L. S. Shackle (1974) and Ludwig M. Lachmann (1986, pp. 89-100 and passim),

who focus on the pervasive uncertainty that enshrouds the future and the

utter baselessness of long-term expectations, impute great significance

to the animal spirts, as they affect the bulls and bears in investment

markets, and to the fetish of liquidity, as it affects their willingness

to make a commitment to either side of any market. Wealth holders are sometimes

more willing, sometimes less willing, to part with liquidity; speculators

are sometimes bullish, sometimes bearish, in their investment decisions.

Such behavior gives rise to continuously changing market conditions and

to a continuously changing pattern of prices. The sequential patterns of

prices in a market economy, predictable by neither economist nor entrepreneur,

are likened to the sequential patterns of cut glass in a kaleidoscope.

There certainly is no reason

to expect, in this vision of the market process, that prices, wage rates,

and interest rates will be consistent with the coordination of production

activities over time or even that they will be consistent with the full

employment of labor at any one point in time. "Keynesian Kaleidics," as

this strand of Keynesianism is sometimes called, is not so much a particular

understanding of the operation of a market economy as a denial that any

such understanding is possible. Clearly, Friedman is not a Keynesian in

this sense.

Interpreters such as John

Hicks (1937) and Alvin Hansen (1947), whose focus penetrated Keynes's cloud

of uncertainty, have identified a set of behavioral relationships which,

together with the corresponding equilibrium conditions, imply determinate

values of total income and the interest rate.(1)

In the most elementary formulation, net investment (I) must equal net saving

(S), and the demand for liquidity (L) must be accommodated by the supply

of money (M). This ISLM framework, more broadly called income-expenditure

analysis, has in many quarters�but not in Austrian ones�come to be thought

of as the analytical apparatus common to all macroeconomic theories. Appropriate

assumptions about the stability of investment and money demand, interest

elasticities, and price and wage rigidities allow for the derivations of

either Keynesian or Monetarist conclusions.

Friedman vs. Keynes

Within the context of income-expenditure analysis, it is appropriate

to think of Friedman's Monetarism as being directly opposed to Keynesianism.

Although both Keynesianism and Monetarists accept the same high level of

aggregation, one which closes off issues believed by the Austrians to be

among the most important, they have sharp disagreements about the nature

of the relationships among these macroeconomic aggregates. Several such

disagreements, many as reported or implied by Friedman (1970), are included

in the following list.

1. Keynesians believe that the interest rate, largely, if not wholly,

a monetary phenomenon, is determined by the supply of and demand for money.

Monetarists believe that the interest rate, largely a real phenomenon,

is determined by the supply of and demand for loanable funds, a market

which faithfully reflects actual opportunities and constraints in the investment

sector.

2. In the Keynesian vision, a change in the interest rate has little

effect on (aggregate) investment; in the Monetarist vision, a change in

the interest rate has a substantial effect on (aggregate) investment. This

difference reflects, in large part, the short-run orientation of Keynesians

and the long-run orientation of Monetarists.

3. Keynesians conceive of a narrowly channeled mechanism through which

monetary policy affects national income. Specifically, money creation lowers

the interest rate, which stimulates investment and hence employment, which,

in turn, give rise to multiple rounds of increased spending and increased

real income. The nearly exclusive focus on this particular channel of effects,

together with the belief that investment demand is interest-inelastic,

accounts for the Keynesian preference for fiscal policy over monetary policy

as a means of stimulating or retarding economic activity. Government spending

has a direct effect on the level of employment; money creation has only

an indirect and weak effect. Monetarists conceive of an extremely broad-based

market mechanism through which money creation stimulates spending in all

directions�on old as well as new investment goods, on real as well as financial

assets, on consumption goods as well as investment goods. Nominal incomes

are higher all around as a direct result of money creation, but with a

stable demand for money in real terms, the price level increases in direct

proportion to nominal money growth so that real incomes are unaffected.

4. Keynesians believe that long-run expectations, which have no basis

in reality in any case, are subject to unexpected change. Economic prosperity

is based on baseless optimism; economic depression, on baseless pessimism.

Monetarists believe that profit expectations reflect, by and large, consumer

preferences, resource constraints, and technological factors as they actually

exist.

5. Keynesians believe that economic downturns are attributable to instabilities

characteristic of a market economy. A sudden collapse in the demand for

investment funds, triggered by an irrational and unexplainable loss of

confidence in the business community, is followed by multiple rounds of

decreased spending and income. Monetarists believe that economic downturns

are attributable to inept or misguided monetary policy. And unwarranted

monetary contraction puts downward pressure on incomes and on the level

of output during the period in which nominal wages and prices are adjusting

to the smaller money supply.

6. Keynesians believe that in conditions of economy-wide unemployment,

idle factories, and unsold merchandise, price and wages will not adjust

downward to their market-clearing levels�or that they will not adjust quickly

enough, or that the market process through which such adjustments are made

works perversely as falling prices and falling wages feed on one another.

Monetarists do not believe that such perversities, if they exist at all,

play a significant role in the market process. They believe instead that

prices and wages can and will adjust to market conditions. The fact that

such adjustments are neither perfect nor instantaneous is, in the Monetarists'

judgment, no basis for advocating governmental intervention. A market process

that adjusts prices and wages to existing market conditions is preferable

to a government policy that attempts to adjust market conditions to existing

prices and wages.

An Austrian Perspective on the Common Language and Apparatus

The contrast between Keynesianism, as interpreted by Hicks and Hansen,

and Monetarism, as outlined by Friedman (Gordon 1974), is based upon their

common analytical framework. The recognition of this common framework underlies

the assessment by Gerald P. O'Driscoll and Sudha R. Shenoy (1976, p. 191)

that "Monetarism... does not differ in its fundamental approach from the

other dominant branch of macroeconomics, that of Keynesianism."(2)

But the Keynesian/Monetarist income-expenditure analysis, no less than

the analysis in Keynes's Treatise on Money, is subject to Hayek's

early criticism. The aggregates conceal the most fundamental mechanisms

of change. While many of the conflicting claims can be reconciled in terms

of the short-run and long-run orientation of Keynesians and Monetarists,

respectively, and in terms of their contrasting philosophical orientations,

neither vision takes into account the workings of failings of the market

mechanisms within the investment aggregate.

Austrian macroeconomics(3)

is set apart from both Keynesianism and Monetarism by its attention to

the differential effects of interest rate changes within the investment

sector, or�using the Austrian terminology�within the economy's structure

of production. A fall in the rate of interest, for instance, brings about

systematic changes in the structure of production. A lower interest rate

favor production for the more distant future over production for the more

immediate future; it favors relatively more time-consuming or roundabout

methods of production as well as the production and use of more durable

capital equipment. The "mechanisms of change" activated by a fall in the

interest rate consist of profit differentials among the different stages

of production. The market process that eliminates these differentials reallocates

resources away from the later stages of production and into the earlier

stages; it gives the intertemporal structure of production more of a future

orientation.

The ultimate consequence

of this capital restructuring brought about by a decrease in the rate of

interest depends fundamentally upon the basis for the decrease. If the

lower rate of interest is a reflection of an increased willingness to save

on the part of market participants, then the capital restructuring serves

to retailor the production process to fit the new intertemporal preferences.

Continual restructuring of this sort�along with technological advancement�is

the essence of economic growth. If, however, the lower rate of interest

is brought about by an injection of newly created money through credit

markets, then the capital restructuring, which is at odds with the intertemporal

preferences of market participants, will necessarily be ill-fated. The

period marked by the extension of artificially cheap credit is followed

by a period of high interest rates when cumulative demands for credit have

outstripped genuine saving. The artificial, credit-induced boom will necessarily

end in a bust.

The Austrian theory of the

business cycle identifies the market process that turns an artificial boom

into a bust. The misallocation of resources within the investment sector

requires a subsequent liquidation and reallocation. The more extensive

the misallocation, the more disruptive the liquidation. After the prolonged

period of cheap credit during the 1920s, for instance, a substantial reallocation

of capital from relatively long-term projects to relatively short-term

ones was essential for the restoration of economic health. A higher than

normal level of unemployment characterized the period during which workers

who lost their jobs in the over capitalized sectors of the economy were

absorbed into other sectors.(4)

Accounting for the artificial

boom and the consequent bust is no part of Keynesian income-expenditure

analysis, nor is it an integral part of Monetarist analysis. The absence

of any significant relationship between boom and bust is an inevitable

result of dealing with the investment sector in aggregate terms. The analytical

oversight derives from theoretical formulation in Keynesian analysis and

from empirical observation in Monetarist analysis. But from an Austrian

perspective, the differences in method and substance are outweighed by

the common implication of Keynesianism and Monetarism, namely that there

is no boom-bust cycle of any macroeconomic significance.

In the General Theory,

the interest rate is sometimes treated as if it depends on monetary considerations

alone, such as in Chapter 14, where Keynes contrasts his own theory of

interest with the classical theory. The supply of and demand for money

(alone) determine the equilibrium rate of interest, which in turn determines

the level of investment and hence the level of employment. The essentially

one-way chain of determinacy makes no allowance for the pattern of saving

and investment decisions to have any effect upon the rate of interest While

this rarified version of Keynesian macroeconomics has not survived the

translation from the General Theory to modern textbooks, it can

by easily represented as a special case of the ISLM construction, one in

which the LM curve is a horizontal line that moves up or down with changes

either in liquidity preferences or in the supply of money. Using more formal

terminology, the system of equations is recursive, such that the rate of

interest can be determined independently of the other endogenous variables.

Within this framework, there is simply no scope for a boom-bust cycle as

envisioned by the Austrians.

In the more general ISLM

framework, the rate of interest and the levels of investment, saving, and

income are determined simultaneously rather than sequentially, but Keynes

downplays any cyclical movements in these magnitudes that might result

from the two-way chains of causation. He emphasizes instead the possibility

of economic stagnation�of enduring secular unemployment. In Chapter 18

of the General Theory, his stocktaking chapter, Keynes envisions

an economy in which there are minor fluctuations of income�and hence

of employment�around a level of income substantially below the economy's

full-employment potential. Only in his "Short Notes Suggested by the General

Theory" does Keynes attempt to account for the cyclical fluctuations considered

inherent in the nature of capitalism. The crises, or upper turning point,

is caused by a change in long-term profit expectations that motivate the

business community�expectations that are "based on shifting and unreliable

evidence" and are "subject to sudden and violent changes" (Keynes, 1936,

p. 315). The recovery, or lower turning point, is governed by the durability

of the capital in existence at the time of the crisis. But in the Keynesian

vision, the economy recovers only to some equilibrium level of unemployment,

not to its full-employment potential.(5)

More tellingly, Keynes perceives

a one-way chain of causation from money supply as a policy variable to

investment (and hence employment) as a policy goal. The monetary authority

increases the money supply; the interest rate falls until money demand

exhausts supply; investment increases, as does employment. A new equilibrium

is established in which the rate of interest is permanently lower and the

levels of investment and employment are permanently higher. In the income-expenditure

framework, the temporal pattern of investment does not enter into the analysis,

and the distinction between a genuine boom and an artificial boom is itself

an artificial distinction.

Friedman's Plucking Model

Keynesian analysis does not disprove the Austrian idea that a credit-induced

boom leads to a bust. By adopting a higher level of aggregation, it simply

fails to bring this issue into focus. Nor is the Austrian idea disproved

by the Monetarists, who rely on a highly aggregated statistical analysis

for clues about the relationship between booms and busts. Levels of aggregate

output that characterize a typical downturn do not correlate well with

a preceding upturn, but the magnitude of the downturn does seem to be related

to the magnitude of the succeeding upturn. In the Monetarists' empirical

analysis, there appears to be a bust-boom, rather than a boom-bust cycle.

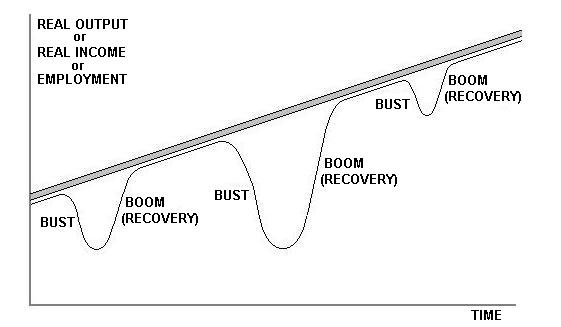

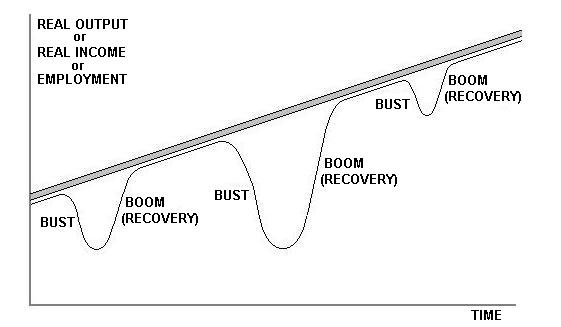

Friedman (1969b, pp. 27-277)

has offered what he calls a "plucking model" of the economy's output over

the period 1879-1961.(6) Imagine a string

glued to the underside of an inclined plane. The degree of incline represents

long-run secular growth in output. If the string were glued at every point

along the inclined plane, it would represent an economy with no cyclical

problems at all. Cyclical problems of the type actually experienced can

be represented by plucking the string downward at random intervals along

the inclined plane. In this representation of the economy's actual growth

path, the economic process that gives us healthy secular growth occasionally

comes "unglued." While the consequent sagging of economic performance is

unrelated to the previous growth, recovery to the potential growth path

is necessarily related to the extent of the sag. But for the slight degree

of incline, there would be a one-to-one relationship between downturn and

subsequent recovery.

On the basis of this Monetarist

representation, the Austrian ideas are rejected, not so much on the basis

of the answers offered, but on the basis of the questions asked. What is

the market process that turns a boom into a bust? There is no empirical

evidence that suggests any such process to be at work. What is the market

process that turns a slump into a recovery? This is the empirically relevant

question, in the Monetarists' view. The suggested answer, which has the

flavor of textbook Keynesianism, involves the conventional operation of

market forces in the face of institutional price and wage rigidities (Ibid.,

p. 274).

As Friedman clearly recognizes,

the dismissal of the possibility of a boom-bust cycle and the empirical

identification of the bust-boom cycle both derive from the inherent asymmetry

of deviations from the potential growth path. The economy's output can

fall significantly below its potential level, but it cannot rise significantly

above it. The fact that Friedman's formulation is in terms of aggregate

output, however, suggests that the Austrian critique of early Keynesianism

is equally applicable to modern Monetarism: Professor Friedman's aggregates

conceal the most fundamental mechanisms of change.

The economy's output consists

in the output of consumer goods plus the output of investment goods. An

artificially low rate of interest can shift resources away from the former

category and into the latter. More importantly, it can skew the pattern

of investment activities toward production for the more distant future;

it can overcommit the investment sector to relatively long-term projects.

Such money-induced distortions are wholly consistent with the changes in

aggregate

output over the nine-decade period studied by Friedman.

In terms of the plucking

model, the Monetarists observe that some segments of the string are glued

fast to the inclined plane and other segments are not. But in terms of

their macroeconomic aggregates, there is nothing in the nature of the string�or

the glue�as we move along a glued section toward an unglued one that explains

why the glue fails. Monetarists instead conceive of the string as plucked

down by some force (an inept central bank) that is at work only on the

segments that constitute the downturn. The Austrians, working at a lower

level of aggregation, examine the makeup of the string (the allocation

of resources within the investment sector) and the consistency of the glue

(the rate on interest and pattern of prices upon which resource allocation

has been based during the boom). They conclude that if the interest rate

has been held artificially low by monetary expansion, the intertemporal

allocation of resources is inconsistent with actual intertemporal preferences

and resource availabilities. The string is destined to become unglued.

Contrasting Theories of Interest

Friedman's plucking model is more notable for the aspects of the market

process it ignores than for the general movements of macroeconomic aggregates

it represents. Movements in the rate of interest and consequences of those

movements for the allocation of resources within the macroeconomic aggregates

play no role in either Monetarism or Keynesianism. In fact, the very choice

of a particular level of aggregation reflects a judgment about which aspects

of the market process are significant enough to be included in macroeconomic

theory. Relationships between the aggregates are significant; relationships

within

the aggregates are not. The aggregates chosen by Keynes were accepted by

Friedman, indicating that the two theorists made the same judgment in this

regard.

Their bases for judgment,

however, are not the same. Opposing views about the nature and significance

of the rate of interest and of changes in that rate underlie the decisions

by Keynes and Friedman to neglect the considerations that are so dominant

in Austrian macroeconomics. All three views can be identified in terms

of the interest-rate dynamics first spelled out by the Swedish economist

Knut Wicksell. The natural rate of interest, so called by Wicksell,

is the rate consistent with the economy's capital structure and resource

base. If allowed to prevail, it would maintain an equilibrium between saving

and investment�and would also keep constant the general level of prices.

The bank rate of interest, by contrast, is a direct result of bank

policy. Credit expansion lowers the bank rate; credit contraction raises

it. Macroeconomic equilibrium can be maintained, according to Wicksell,

only by a monetary policy that keeps the bank rate equal to the natural

rate.(7) Therefore, a banking system that

pursues a cheap-credit policy (by holding the bank rate of interest below

the natural rate) throws the economy into macroeconomic disequilibrium.

While the Austrians, beginning

with Mises (1971), adopted Wicksell's formulation as the basis for their

own theorizing, deviating from it only in terms of the consequences of

a credit-induced macroeconomic disequilibrium, neither Keynesians no Monetarists

share Wicksell's concern about the relationship between the bank rate and

the natural rate. In summary terms, Keynes denied that the concept of the

natural rate had any significance; Friedman, who accepts the concept, denies

that there can be deviations of any significance from the natural rate.

Although Keynes had incorporated

a modified version of Wicksell's natural rate in his Treatise on Money,

he could find no place for it in his General Theory. In the earlier

work, full employment was the norm; and the (natural) rate of interest

kept investment in line with available saving. In the later work, the rate

of interest is determined, in conjunction with the supply of money, by

irrational psychology (the fetish of liquidity), and the level of employment

accommodates itself to that interest rate. Keynes argued that " there is

... a different natural rate of interest for each hypothetical level

of employment" and concluded that "the concept of the 'natural' rate of

interest ... has [nothing] very useful or significant to contribute to

our analysis" (Keynes 1936, pp. 242-43).

In Friedman's Monetatism,

competition in labor markets gives rise to a market-clearing wage rate,

which singles out from Keynes's hypothetical levels of employment the one

level for which labor supply is equal to labor demand. The concept of the

natural rate of interest, that is, the rate that clears the loan market

and keeps investment in line with savings, fits as naturally into the Monetarists'

thinking as it fits into Wicksell's. In fact, Friedman coined the term

"natural rate of unemployment" to exploit the similarity between the Wicksellian

analysis of the loan market and his own analysis of the labor market (Friedman,

1976, p. 228). According to Wicksell, a discrepancy between the bank and

the natural rates of interest gives rise to a corresponding discrepancy

between

saving and investment; according to Friedman, a discrepancy between the

actual and the natural rates of unemployment reflects a corresponding discrepancy

between the real wage rate, as perceived by employers, and the real wage

rate, as perceived by employees. Macroeconomic disequilibrium plays itself

out in ways that eventually eliminate such discrepancies in loan markets

(for Wicksell) and in labor markets (for Friedman).

While the Wickesll-styled

dynamics in labor markets have been of some concern to Monetarists, the

corresponding loan-market dynamics play no role at all in Monetarism. The

bank rate of interest never deviates from the natural rate for long enough

to have any significant macroeconomic consequences. Whatever effects there

are of minor and short-lived deviations are trivialized by Friedman as

"first-round effects" (Gordon, 1974, pp. 146-48). That is, the initial

lending of money, the first round, is trivial in comparison to the subsequent

rounds of spending, which may number twenty-five to thirty per year. Friedman

summarily dismisses all such interest-rate effects, as spelled out by modern

Keynesians (Tobin) and by Austrians (Mises), and affirms that his own macroeconomics

is characterized by its according "almost no importance to first-round

effects" (Ibid., p 147).

Austrian macroeconomics

is distinguished from the macroeconomics of both Keynes and Friedman by

its acceptance of the Wicksellian concept of the natural rate and by its

attention to the consequences of a bank-rate deviating from the natural

rate. It is distinguished from Wicksellian macroeconomics, however, in

terms of the particular consequences taken to be most relevant. For Wicksell

(1936, pp. 39-40 and passim), a deviation between the two rates

puts upward pressure on the general level of prices. If, for instance,

the natural rate rises as a result of technological developments, inflation

will persist until the bank rate is adjusted upward. A relatively low bank

rate may create "tendencies" for capital to be reallocated in ways not

consistent with the natural rate, but those tendencies do not, in Wicksell's

formal analysis, become actualities. Real factors continue to govern the

allocation of capital, while bank policy affects only the general level

of prices (Ibid., pp. 90 and 143-44). But because both the Swedish

and the Austrian formulations are based upon Böhm-Bawerkian capital

theory, the particular "tendencies" identified by Wicksell correspond closely

to the most relevant "mechanisms of change" spelled out by Hayek. Also,

Wicksell's informal discussion, which accompanies his formal exposition,

gives greater scope for actual quantity adjustments within the capital

structure (Ibid., pp. 89-92).

For the Austrians, the effects

of a cheap-credit policy on the general level of prices is, at best, of

secondary importance. If in fact the discrepancy between the two rates

of interest is attributable to technological developments, as Wicksell

believed it to be (Ibid., p. 118), then the resulting increase in

the economy's real output would put downward pressure on prices, largely,

if not wholly, offsetting the effect of the credit expansion on the price

level. If, alternatively, the discrepancy is more typically attributable

to inflationist ideology, as Mises (1978a, pp. 134-38) came to believe,

then, in the absence of any fortuitous technological developments, the

credit expansion would put upward pressure on prices in general. Still,

this general rise in prices, this fall in the purchasing power of money,

is of less concern to the Austrians than the changes in relative prices

that result from the artificially low bank rate of interest.

The "tendencies" for reallocation

within the capital sector acknowledged by Wicksell become "actualities"

in the Austrian view. The market process is not so fail-safe as to preclude

any investment decision not consistent with the overall resource constraints.

Newly created money put into the hands of entrepreneurs at an artificially

low interest rate allows them to initiate production processes that eventually

conflict with the underlying economic realities (Hayek, 1967c, pp. 69-100).

Where Wicksell claimed that tendencies toward reallocation do not become

actualities, the Austrians claim that actual reallocations induced by credit

expansion are unsustainable. The artificial boom ends in a bust.

In his discussion of Keynesian

and Austrian concerns about interest-rate effects, Friedman claims that

the importance of ultimate effects, as compared to first-round effects,

is an empirical question (Gordon 1974, p. 147). The Austrians recognized

that ultimately, after boom, bust, and recovery, empirical analysis

would reveal no lingering effects of the initial credit expansion on the

bank rate of interest relative to the natural rate. The economy overall

would be less wealthy for having suffered a boom-bust cycle, and hence

the natural rate itself might well be higher. But the relative magnitudes

of the initial and ultimate effects is no basis for ignoring the market

process that produced them. The first-round effects constitute the initial

part of a market process that plays itself out within capital and resource

markets; the loss of wealth and possible increase in the natural rate is

the ultimate effect of that same market process.

The Dynamics of an Unsustainable Boom

Although Friedman does not engage in process analysis in his treatment

of the interest rate as it is affected by credit expansion, he does engage

in process analysis in his treatment of the wage rate as it is affected

by price-level inflation (Friedman, 1976, pp. 221-29). The first-round

effects consist of a discrepancy between two wage rates: the rate as perceived

by the workers and the rate as perceived by the employer. Such a discrepancy

occurs in the early phase of an inflation because the employer immediately

perceives the difference between the price he pays for labor and the newly

increased price of the one product he produces, while workers perceive,

but belatedly, the general increase in the prices they pay for consumer

goods The ultimate effect of price-level inflation is a rising nominal

wage rate, which maintains a real wage rate�as perceived (correctly) by

both employers and workers�consistent with the natural rate of unemployment.

Friedman could have made

the claim, in connection with these labor-market dynamics, that "the importance

of the ultimate effects in comparison to the first-round effects is an

empirical question." Undoubtedly, direct empirical testing�if data could

be obtained on the differing perceptions of wage rates�would show the ultimate

effects to be dominant. But Friedman does not dismiss his own analysis

with a rhetorical question about an empirical test. Instead, he sees the

first-round effects as the initial part of a market process that plays

itself out within labor markets, and he sees the reestablishment of the

natural rate of unemployment as the ultimate effect of that same process.

There is empirical evidence

consistent with both the Monetarist treatment of labor markets and the

Austrian treatment of credit markets. The unsustainablility of an inflation-induced

boom in labor markets and of a credit-induced boom in capital markets is

suggested by a natural rate of interest and a natural rate of unemployment

that are independent of monetary policy. Data on inflation rates and unemployment

rates for the last several decades must be accounted for in terms of some

market process through which monetary expansion has an initial effect,

but not a lasting one, on real magnitudes. Whether the most relevant market

process is one working through labor markets or one working through credit

markets is a matter of logical consistency, plausibility, and historical

relevance.(8) And, of course, Monetarist

labor-market dynamics and Austrian capital-market dynamics can be seen

as partial, complementary accounts of the same, more broadly conceived

market process.

This comparison of Monetarism

and Austrianism in the context of the dynamics of an unsustainable boom

seems to create an alliance between these two schools against Keynesianism.

The allied account of an artificial boom that contains the seeds of its

own destruction stands in contrast to the Keyensian account of a bust attributable

to a sudden and fundamentally unexplainable loss of confidence in the business

community. But the alliance is only a tactical one. Any theory of a boom-bust

cycle is inconsistent with Friedman's plucking model, which suggests that

there are no such cycles to be explained.

The original context in

which Friedman offered his account of the inflation-induced labor market

dynamics makes the inconsistency understandable. Friedman was not attempting

to identify a market process that fits neatly into his own Monetarism.

Instead, he was demonstrating the fallacy of a politically popular Keynesian

belief that there is a permanent trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

Based upon the empirical study done by A. W. Phillips in the late 1950s,

many Keynesians came to believe that the inverse relationship between rising

nominal wages and unemployment constituted a menu of social choices and

that policymakers should acknowledge the preferences of the electorate

by moving the economy to the most preferred combination of inflation and

unemployment.

Friedman was willing to

do battle with the Keynesian optimizers on their own turf. Accounting

for the inverse relationship in terms of a misperception of wages, he was

able to show that the alleged trade-off existed only in the short run and

therefore did not constitute a sound basis for policy prescription. There

is no evidence, however, that he considered these labor-market dynamics

to be an integral part of his own macroeconomics, although some Monetarists,

notably Edmund S. Phelps (1970), and most textbook writers have taken them

to be just that.(9) Neither Keynesianism,

as represented by ISLM analysis, nor Monetarism, as represented by Friedman's

plucking model, acknowledges the boom-bust cycle as a part of our macroeconomic

experience. Austrianism is set apart from the other two schools in this

regard. And, by adopting a fundamentally different framework at a lower

level of aggregation, the Austrians have been able to identify the capital-market

dynamics essential to the understanding of such cycles.

A Summary Assessment: The Wicksellian Watershed and the Austrian

Sieve

In the broad sweep of the history of macroeconomic thought, the Wicksellian

theme, in which there can be a temporary but significant discrepancy between

the bank rate and the natural rate of interest, constitutes an important

watershed. A significant portion of twentieth-century macroeconomics can

be categorized as variations of this Wicksellian theme. Included indisputably

in this category are followers of Wicksell in Sweden: Gustav Cassel, Eric

Lindahl, Bertil Ohlin, and Gunner Myrdal; Wicksell-inspired theorists in

Austria: Ludwig von Mises and, following him, F. A. Hayek; and British

theorists working in the tradition of the Currency school: Ralph Hawtrey,

Dennis Robertson, and taking his cue from the Austrians, the early Lionel

Robbins.

Excluded from this category

are those theorists who deny, ignore, or downplay the Wicksellian theme,

typically by adopting a level of macroeconomic aggregation too high for

that theme, in any of its variations, to emerge. Exemplifying these theorists

are Irving Fisher and, following him, Milton Friedman. Even Don Patinkin,

who draws heavily on Wicksell's ideas about the dynamics of price-level

adjustments, belongs to this group. His chosen level of aggregation, which

combines consumer goods and investment goods into a single aggregate called

commodities, precludes from the out set any non-trivial consequence of

the discrepancy between the bank rage and the natural rate.

Axel Leijonhufvud (1981,

p. 123) bases his own interpretation of Keynes on a similar grouping of

theorists. Wicksell and Fisher are at the headwaters of two separate traditions

labeled "Saving-Investment Theories" and "Quantity Theory." Leijonhufvud

makes Keynes out to be a Wicksellian, but he does so only by patching together

a new theory with ideas taken selectively from the Treatise and

the General Theory. This interpolation between Keynes's two books

is designated "Z-theory" (Ibid., pp. 164-69). Drawing from the first book,

it allows for a natural rate of interest from which the bank rate can diverge,

and

drawing from the second book, it allows for the resulting disequilibrium

to play itself out through quantity adjustments rather than through price

adjustments.

Leijonhufvud's hybrid Keynesian

theory gives play to the Wicksellian theme and fits comfortably in the

list of "Saving-Investment" theories. With the exposition of his "Z-theory,"

Leijonhufvud has clearly identified himself as a Wicksellian.(10)

To claim, however, that Keynes himself was a Wicksellian is to engage in

counter-factual doctrinal history. In the Treatise, the discrepancy

between the bank rate and the natural rate did not have a significant effect

on the saving-investment relationship; in the General Theory, significant

disturbances to the saving-investment relationship were not attributed

to a discrepancy between the two rates.

By offering his Z-theory

in support of Keynes's candidacy as a Wicksellian, Leijonhufvud tacitly

admits that Keynes had actually managed to skirt the Wicksellian idea first

on one side, then of the other. The categorization of theorists defended

in this chapter differs importantly from Leijonhufvud's in that Keynes

is transferred�on the basis of what he actually wrote�to the other side

of the Wicksellian watershed. Keynes's chosen level of aggregation, together

with his neglect of Wicksellian capital-market dynamics, establishes an

important kinship to Fisher, Friedman, and Patinkin.

Hayek's early "Reflections

on the Pure Theory of Money" might well have been entitled "Is Keynes a

Quantity Theorist?" Nearly half a century after his critique of the Treatise,

Hayek explicitly categorized "Keynes's economics as just another branch

of the centuries-old Quantity Theory school, the school now associated

with Milton Friedman" (Minard, 1979, p. 49). Keynes, according to Hayek,

"is a quantity theorist, but modified in an even more aggregative or collectivist

or macroeconomic tendency" (Ibid.).

The Wicksellian watershed,

as employed by Leijonhufvud, makes a first-order distinction between broad

categories of theories on the basis of subject matter. In one category,

the subject is saving and investment and the market process through which

these macroeconomic magnitudes are played off against one another. In the

other category, the subject is the quantity of money and the market process

through which changes in the supply of or demand for money affect other

real and nominal macroeconomic magnitudes.

An alternative first-order

distinction, more in the spirit of Hayek's critique of Keynes, is one based

on alternative levels of macroeconomic aggregation. The notion of a Wicksellian

watershed might well be supplemented by the notion of an Austrian sieve.

In one broad category of theories, the level of aggregation is low enough

to allow for a fruitful exploration of the Wicksellian theme. In the other

category, the level of aggregation is so high as to preclude any such exploration.

Based on their high levels of aggregation, then, both Keynesianism and

Monetarism fail to pass through the Austrian sieve. This is the meaning

of Hayek's claim that Keynes is a quantity theorist and of the corresponding

claim that Friedman is a Keynesian.

Bibliography (to be added)

Notes

1. This interpretation is almost universally

attributed to Hicks (on the basis of his early article) and to Hansen (on

the basis of his subsequent exposition). Warren Young (1987) makes the

case that, on the basis of the papers presented at the Oxford conference

in September 1936, credit for the ISLM formulation should be shared by

John Hicks, Roy Harrod, and James Meade.

2. Friedman clearly recognizes his

kinship to Keynes in terms of their fundamental approach: "I believe that

Keynes's theory is the right kind of theory in its simplicity, its concentration

of a few key magnitudes, its potential fruitfulness. I have been led to

reject it not on these grounds, but because I believe that it has been

contracted by experience" (Friedman, 1986, p. 48). Allan H. Meltzer identifies

the type of theorist that produces Keynes's kind of theory: "Keynes was

the type of theorist who developed his theory after he had developed a

sense of relative magnitudes and of the size and frequency of changes in

these magnitudes. He concentrated on those magnitudes that changed most,

often assuming that others remained fixed for the relevant period" (Meltzer,

1988, p. 18). This method is not as laudable as it may seem. If subtle

changes in credit and capital markets induce significant but difficult-to-perceive

changes in the economy's capital structure, then Keynes's�and Friedman's�method

is much too crude. Surely, the job of the economist is to identify market

processes even when�or especially when�the relevant market forces do not

have direct or immediate consequences for some macroeconomic aggregate.

3. Austrian macroeconomic relationships

are spelled out in various contexts by Ludwig von Mises (1966), F. A. Hayek,

(1967), Lionel Robbins (1934), Murray Rothbard (1970, 1983), Gerald P.

O'Driscoll, Jr. (1977), and Roger Garrison (1989, 1986).

4. The aphorism "the bigger the boom,

the bigger the bust" must be applied cautiously. The Austrian theory links

the necessary, or unavoidable, liquidation to the credit-induced misallocations.

It does not imply, as, for example, Gordon Tullock (1987) seems to believe,

that all the actual liquidation during the Great Depression is to be explained

with reference to misallocations that characterized the previous boom.

Much, if not most, of the liquidation during the 1930s can be attributed,

as Rothbard (1983) indicates, to misguided and perverse macroeconomic and

industrial policies implemented by the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations

5. The relative emphasis on secular

unemployment, as compared to cyclical unemployment, is consistent with

Meltzer's interpretation of Keynes (Meltzer, 1988, pp. 196-210). In most

modern textbooks, involuntary unemployment is taken to mean cyclical unemployment.

In Meltzer's view, which is more faithful to the General Theory

and to Keynes's long-held beliefs about capitalistic economies, cyclical

unemployment is a minor component of involuntary unemployment (Ibid.,

p. 126).

6. Although there is no explicit reference

to Hayek or other Austrian theorists in his article, the plucking model

is clearly intended as a basis for rejecting the general category of theories

which account for the boom-bust cycle.

7. It is recognized both by modern

Austrian theorists and by Wicksell's contemporaries that the equivalence

of the bank rate and the natural rate is consistent with price-level constancy

only in the special case of constant output. If the economy is experiencing

economic growth, then maintaining a saving-investment equilibrium will

put downward pressure on prices, and conversely, maintaining price-level

constancy will cause investment to run ahead of saving.

8. An assessment of the logical consistency,

plausibility, and historical relevance of these two perspectives on monetary

dynamics is undertaken in Bellante and Garrison (1988).

9. Friedman's Wicksell-styled analysis

of labor-market dynamics stands in direct conflict with his fourth-listed

Key Proposition of Monetarism, according to which "the changed rate of

growth of nominal income [induced by a monetary expansion] typically shows

up first in output and hardly at all in prices" (Friedman, 1970, p. 23).

In his subsequent Phillips curve analysis, misperceived price increases

precede

and are the proximate cause of increases in output. For an extended discussion

of this inconsistency, see Birch et al. (1982); for an attempt at

reconciliation, see Bellante and Garrison (1988, pp. 220-21).

10. But "Leijonhufvud the Wicksellian"

remains a puzzle to modern Austrian economists. In his exposition of the

Wicksellian theme, Leijonhufvud grafted Wicksell's credit-market dynamics

onto neoclassical capital theory and appended the following note: "Warning!

This is anachronistically put in terms of a much later literature on neoclassical

growth. Draining the Böhm-Bawerkian capital theory from Wicksell will

no doubt seem offensively impious to some, but I do not want to burden

this paper also with those complexities" (Leijonhufvud, 1981, p. 156).

Then, in his restatement of the critical arguments, Leijonhufvud reveals

his own judgment on natters of capital theory: "Like the Austrians,...I

would emphasize the heterogeneity of capital goods and the subjectivity

of entrepreneurial demand expectations." If Leijonhufvud had emphasized

Austrian capital theory as the stage on which the Wicksellian theme was

to be played out, he would have left Keynes in the wings and followed that

theme from Wicksell to Hayek.

|

He Isn't

But He Is

He Isn't

But He Is