of

The founders of what would become Auburn University and the College of Agriculture were not about waiting. That’s why, several years before the formal establishment of an agricultural experiment station, they were already declaring the mission of such an institution and carrying it out, albeit with limited funds. The state formally established an agricultural experiment station on Feb. 23, 1883, making Alabama the ninth state to do so.

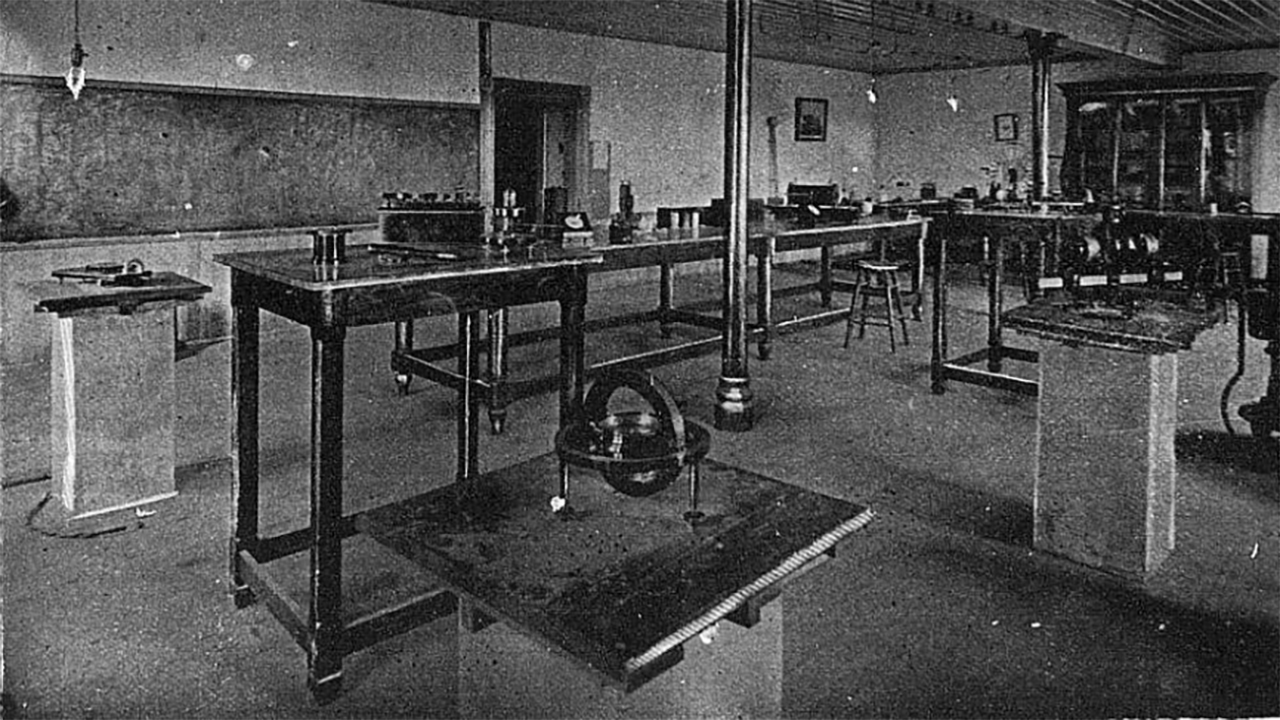

While America celebrated its 116th birthday, a handful of students attended the first electrical engineering class in Auburn history in the basement of what is now Samford Hall.

On Friday, Nov. 8, 1895, as Auburn’s football team rode north to Nashville for its inaugural game under head coach John Heisman, the world changed. Word of what German mechanical engineer Wilhelm Röntgen had first seen in his laboratory — that morning in America, that evening in Würzburg — began popping up across the Atlantic the first week of January 1896. Newspapers began running brief but tantalizing tales about some sort of “new photography.”

It’s an anomaly on the Auburn University campus — a small plot of land that essentially looks as it always has for more than 100 years, even as a major research university has sprung up around it. In the shadow of an 88,000-seat football stadium and other multimillion-dollar structures sits the 1-acre Old Rotation. And less than one mile away sits an equally unassuming 2-acre field, adjacent to — of all things — a world-class art museum: The Cullars Rotation.

Any list of the most recognizable architecture of Auburn University would be incomplete without Comer Hall. Originally completed in 1910, the building has long been a favorite campus landmark for alumni not only because it was, for decades, the center for most of the College of Agriculture’s activity, but it also is unlike any other architecture on campus.

Paul Turnquist was in the 15th year of his 21-year tenure as head of Auburn University's agricultural engineering department in 1992. Things were good. They had been good for a while. Some of the faculty's recent research into alternative energy production via solar power and even animal waste was downright groundbreaking.

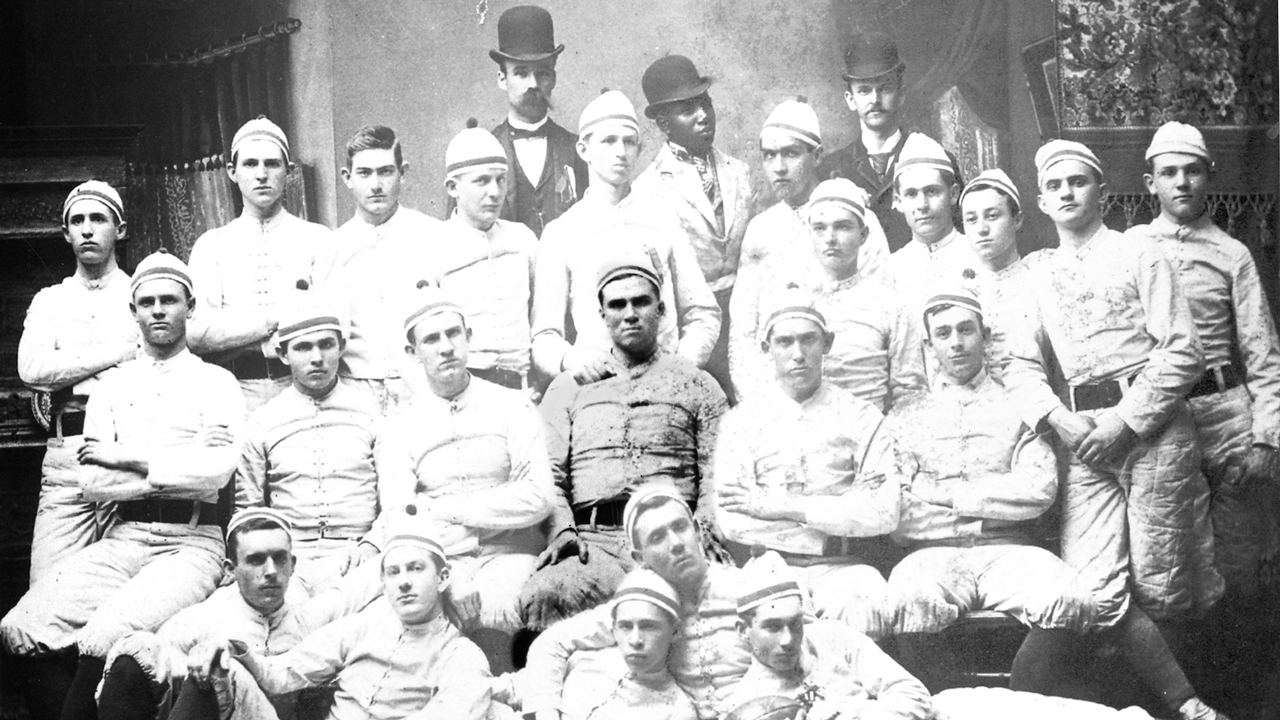

In 1892 — the very same year the Alabama A and M College football team played the University of Georgia in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park in its very first football game and three young women crossed the threshold of Samford Hall to become the Auburn college’s first female coeds — a far less heralded event quietly took place many miles away in Texas that would have a much more shocking effect on Alabama, Auburn and the Deep South as a whole.

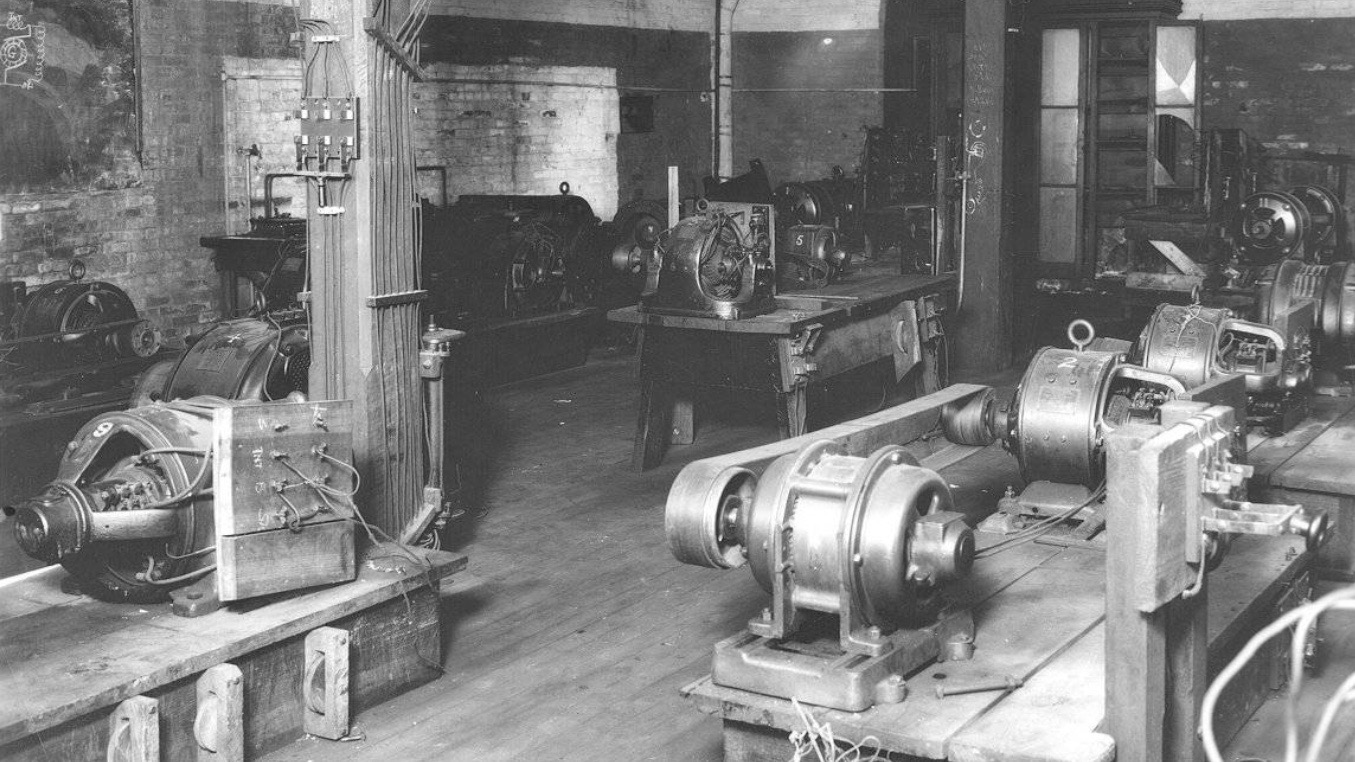

It seems strange to think about now, in an era when electricity powers so many things in our modern lives — from smartphones and computers to increasing numbers of automobiles — but the idea of electrical power was not always greeted with enthusiasm. In fact, in the 1920s, as electrification became increasingly common in Alabama’s cities and towns, many of the state’s farmers and rural residents viewed this new-fangled technology with outright suspicion, if not open hostility.

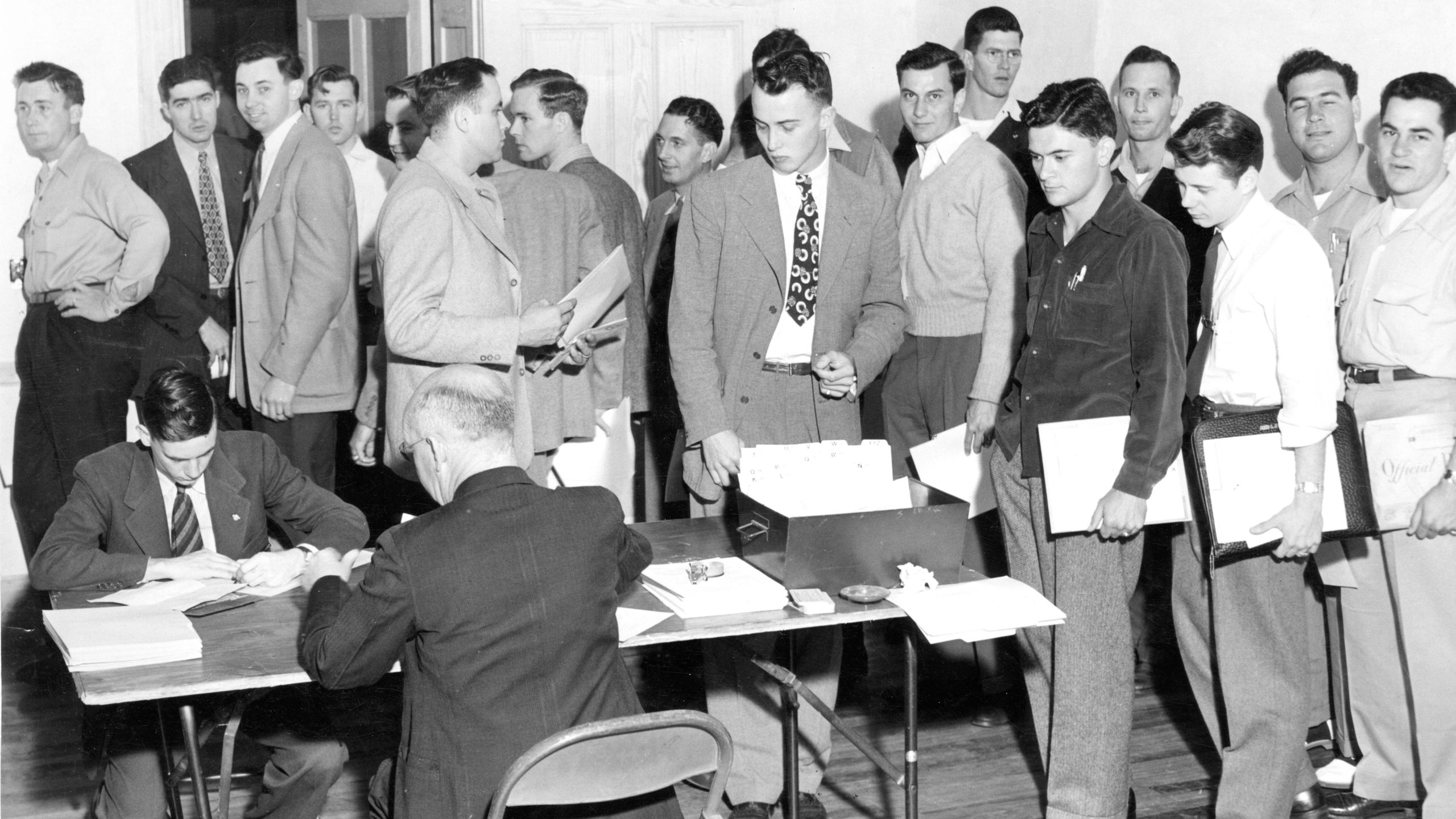

Imagine it. You’re 21 years old, and you’ve been told to report to the basement of Samford Hall. You’re going to war. On Dec. 12, 1941 — five days after the Japanese military surprise attack on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii — registered male students at Alabama Polytechnic Institute who were 21 and older dutifully assembled in said basement and provided information on their status in Selective Service.

On the heels of the Wright Brothers’ success at Kitty Hawk, the late Charles R. Hixon, a mechanic arts postgraduate student, spoke on the “Possibilities of Aerial Navigation” to Alabama Polytechnic Institute engineering students in 1909, stirring interest in this new-fangled concept.

Auburn’s original “fishermen” — men like E.V. Smith, H.S. Swingle and E.W. Shell — laid the foundation for what eventually became the College of Agriculture’s Department of Fisheries and Allied Aquacultures. In doing so, they followed an almost Biblical quest in using the science of fish farming to help feed Alabama and the world.

Although it took a while for the game of golf to work its way to Alabama — the first ever 18-hole course opened in St. Andrews, Scotland, in 1764 and Alabama got its first course at the Country Club of Birmingham in 1903 — the search for a better turfgrass for both sporting venues and home lawns and gardens has been an ongoing one in the Auburn University College of Agriculture for many years.

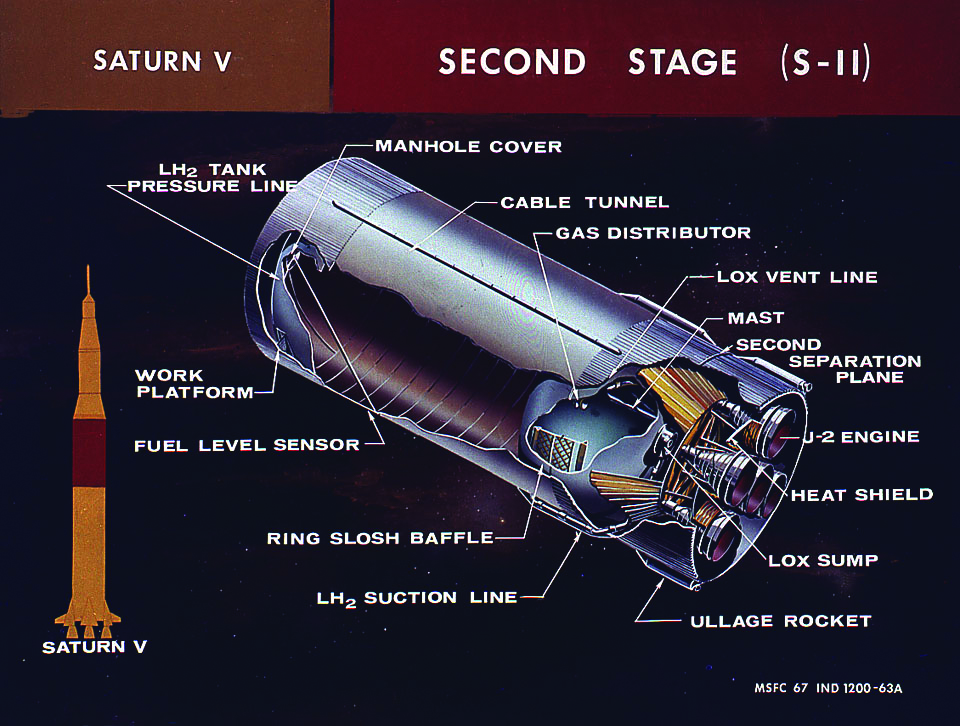

It would be perfect. The Eagle would land. The “War Eagle” would be heard. It wasn’t a joke. It was a promise. And Cliff “C.C.” Williams’ friends believed him. After all, the lunar module that the 1954 Auburn mechanical engineering graduate spent his days perfecting had been dubbed the Eagle, and he was still a huge football fan.

5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, all engines running…liftoff, we have a liftoff. These words echoed around the world as Jack King, Kennedy Space Center’s chief of public information, narrated the events of July 16, 1969.

Raucous celebrations on Earth were fading into the early morning hours of July 21, 1969, as Jim Odom stepped outside his Decatur home and cast his eyes toward Earth’s closest neighbor – the moon. Like millions of other Americans, Odom had watched with rapt attention as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin of the Apollo 11 mission made “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” on the lunar surface earlier in the evening.

Like a lot of great discoveries, PGPR, or plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, came about when someone wasn’t particularly looking for it. This “unintentional” discovery has evolved into a technology that is becoming a standard input in crop production and has spawned numerous other groundbreaking research projects across several disciplines.

In the decades that built up to the turn of the century, the College of Engineering was administered by a progression of leaders who aligned its programs with the changing face of technology, teaching methods, research needs and career opportunities.

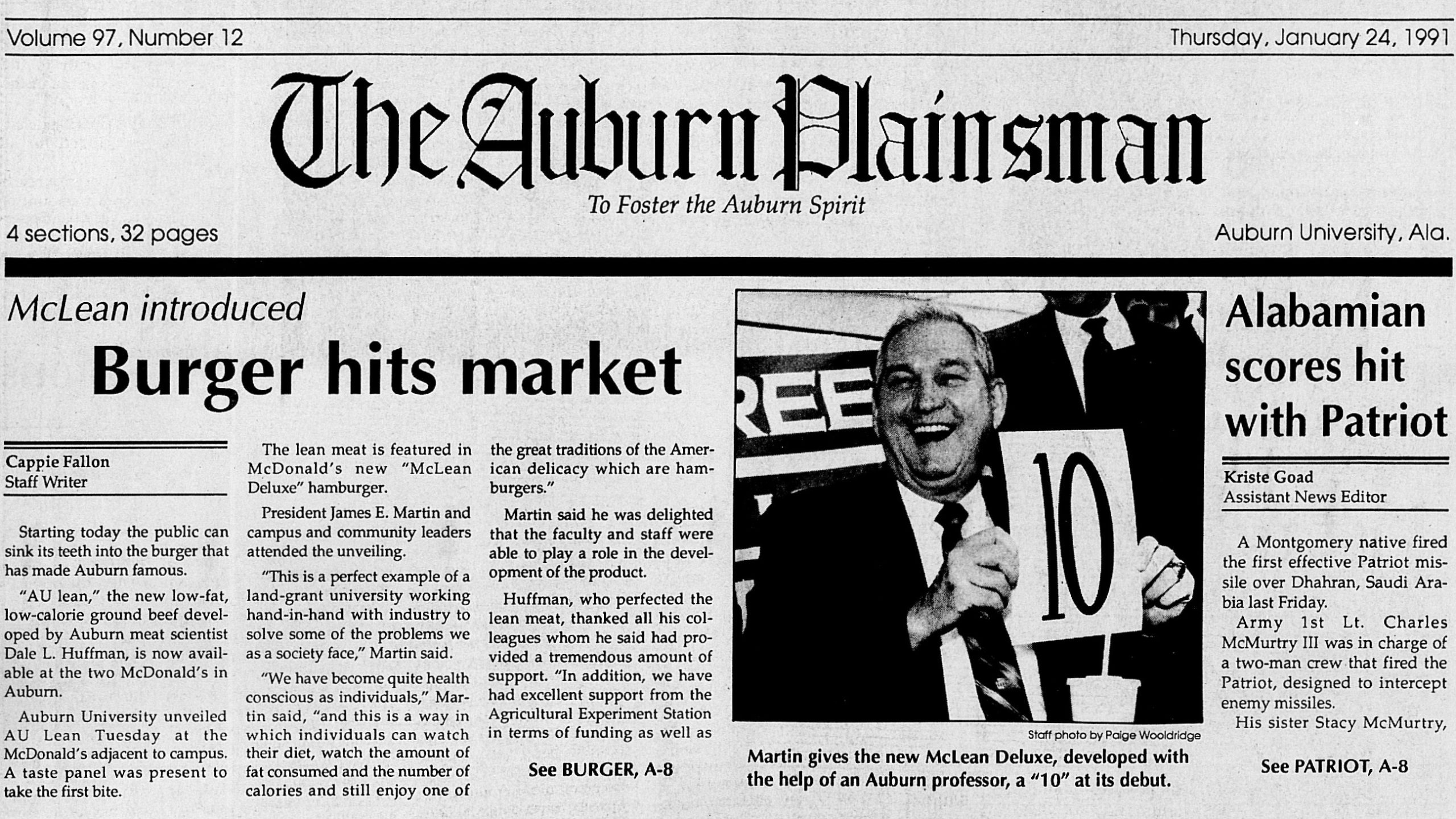

In an era when meat derived entirely from plants has become increasingly mainstream and such products are available everywhere from fast food outlets to your local grocery store, it is worth a look back at the role the Auburn College of Agriculture — and Auburn researchers Dale Huffman and Russ Egbert — played in the early search for a healthier meat alternative, long before the current craze began.

It was in the early morning hours after a big Tiger football win that an angry fan from another SEC school decided to put an end once and for all to the hallowed Auburn tradition of rolling the 80-year-old live oaks at Toomer’s Corner with toilet paper in recognition of a major sports victory. Killing the trees, he thought, would put an abrupt end to the tradition. In a way, the failed attempt on Auburn’s beloved oaks was a blessing in disguise.

In 2008, Phase I of the complex was completed and became the new home to the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering and the Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering. The center also houses administrative offices, the Office of Student Services and the Alabama Power Academic Excellence Program, as well as a 150-seat auditorium and a number of computer classrooms, laboratories and student study galleries.

His biggest dream, always, was to teach at Auburn... It was a dream that came true for Larry Benefield in 1979 — one that took seed in the early 1960’s when the graduate from rural Handley High School showed up on the Auburn campus as a freshman.

Growing up in the small town of St. Genevieve, Mo., Chris Roberts was surrounded by music — more importantly, by musical instruments. His father owned a music store and it was where Roberts hung out after school. His favorite part was fiddling around with the instruments, a pastime that would largely influence his career choice and chart the course for where he is today — dean of the Samuel Ginn College of Engineering at Auburn University.